Is Muscle Memory Real?

So it turns out that muscle memory really is a thing! This bit of lingo has been thrown around for a long time. Muscle memory is usually used to reference the learning process your body goes through when you practice athletic activities. Of course, not everyone believed it to be a real. How can muscles have a memory? But a landmark scientific study recently showed that muscles can actually “remember” prior bouts of exercise. And they can use that memory to respond better to exercise in the future. Muscle memory from weight lifting is real!

So now the interwebs have been abuzz with every fitness media outlet claiming that “we knew it all along!” “Muscle Memory is a real thing!” “You really do have muscle memory!” Of course, the chorus of “I told you so” is a little disingenuous. None of these recent findings have anything to do with how we have previously defined muscle memory. But that doesn’t make this new understanding of biology any less breathtaking in its implications. I’m cool with a little retcon if it gets the word out!

What we have traditionally called muscle memory is actually subconscious automation of complex motions. That happens in the part of your brain responsible for making your intentional movements actually happen. That portion of the brain is called the cerebellum. Ingraining these patterns requires practice and repetition. But it’s how we become adept at sports and playing musical instruments. Consider, as an example, learning the clean or snatch.

Learning this complex technique requires thought and intention at first. You have to be purposeful in your movement and think about correcting deficits. But with repetition, it becomes second nature. Your cerebellum automates the proper sequence of muscle activation. You stop having to think about it. You develop “muscle memory.”

But now we find that muscles actually do have a memory of sorts. And it’s entirely different from any memory stored in your brain. In fact, it’s entirely different from “muscle memory” as we’ve ever used the term before. (From here on out, it would probably help if you imagine Morgan Freeman or David Attenborough narrating this post!)

Of course, this isn’t a memory in the traditional sense. Rather, it is a long-lasting alteration of the very DNA of the muscle cells. That process is known as “epigenetics.” The true fitness geeks can read more about the topic of epigenetics in this article on Wikipedia.

For the rest of the readers, I’ll summarize it for you. When a gene is active, the body copies the genetic code to use as a template for making proteins. But your body can modify genes. It can put a tiny methyl tag at the start of each one, modifying its behavior. It changes which protein each cell produces. And ultimately this is how we end up with so many different cells: liver, kidney, muscle, etc.

How Does Muscle Memory Work?

Tagging a gene is sort of like putting a strip of tape over a light switch that you don’t want anyone to use. It doesn’t change your genetic code at all. And when you pull the tape off, the switch can be turned on and the gene starts working again. Of course, sometimes you can tape the switch in the “on” position as well. And the same is true for your genes. This is the key to understanding the new “muscle memory.”

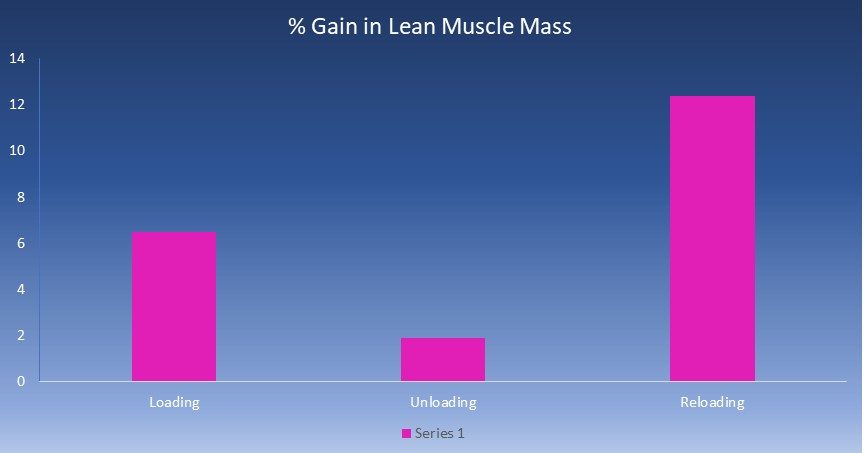

So how did the study by Seaborne prove that muscles remember exercise? Well, you can read the entire study online here. But in short, they took a group of people and had them exercise for 7 weeks, 3 days a week. Then they let them rest for seven weeks. And finally, they returned them to the exercise program for another seven weeks. After each seven-week session, they measured lean body mass and took muscle biopsies. And the results were frankly astounding.

Does Muscle Memory Help Regain Muscle Mass?

As expected, seven weeks of exercise improved the subjects lean muscle mass. And likewise, seven weeks of rest returned them to their old, significantly-less-well-muscled physique. But the final seven weeks showed something unexpected, at least to most of us.

After the second period of exercise, the subjects had not only recovered their prior muscle mass. That had, in fact, exceeded those gains! And not by a small margin. It was nearly double! So muscle memory takes at least 7 weeks to go away. And since there was no notable drop in the DNA markers of memory in that 7 weeks, I’d expect they last far longer.

And the DNA testing from the muscle biopsies showed exactly what the researchers were hoping to find: The amount of DNA modification had changed by a considerable degree. Over 17,000 genes showed modification of their epigenetic tags! And even after seven weeks of rest, nothing had changed. Those genes were still “tagged” differently after nearly two months away from the gym! The muscles “remembered” the exercise challenge by modifying their DNA, and kept those changes going.

But that wasn’t all. The second round of exercise showed even more DNA modification. Over 27,000 genes had modified tags. This correlates with the rapid hypertrophy of muscle seen after the second set of exercise. And ultimately it shows that muscle cells can modify their DNA to “remember” prior bouts of exercise. Once set, this muscle memory persists for quite some time. And it prepares the body to respond even better to exercise in the future.

How Can Muscle Memory Help You?

What does all of this scientific information mean to you? Well, this lets us know that rest is not only necessary but can be very beneficial. Not surprisingly, a couple of our articles have stressed the importance of recovery and sleep. I’ve often told athletes and patients that taking a break can be good for them. Returning to sports after a break seems to restart your engines. Seems like I wasn’t the only one to notice this phenomenon.

A couple caveats of course. While this study is exquisitely designed and executed, I always want to see somebody replicate the results. And it would be awesome to use this study method with trained athletes. But still, we are cautiously amazed by the results. This is really the kind of study design that more research should emulate.

Another caveat: seven weeks is a long time off. After two months off a lot of people might lose the gym habit. So I wouldn’t recommend the average person adhere strictly to this program. You might walk out the door and forget to come back. Maybe the typical gym addict should go heavy for a couple months and then decrease the weights and intensity for a couple months. Then get back to grinding and see how your body responds!

The other implication here is that it’s better to treat your injuries properly rather than push through them. As the saying goes, life is one damned thing after another. But if you have an injury, surgery, or other life emergencies it’s okay. You don’t have to worry about your missed time at the gym. Those PRs will still be waiting for you. And they may be easier to achieve than ever before!

Works Cited

Seaborne, Robert A., et al. “Human Skeletal Muscle Possesses an Epigenetic Memory of Hypertrophy.” Scientific Reports Jan 2018