Why do you get so strong so quickly when you start working out?

Why do your gains slow down so much after you exercise for a while? Why are PR’s so easy when you start lifting and so hard later? This weeks post is all about answering these fundamental questions. As a gym owner or coach, you’ll see this a lot. And you’ll have to deal with athletes that get frustrated as their gains slow down. You need to be able to answer that ever-present question. “What happened to me? Why aren’t I getting stronger?” It all comes down to the neurologic adaptations to strength training.

As time goes on, it’s totally normal for an athletes improvements to taper off and slow down. Wouldn’t it be awesome if those gains could be made throughout your entire weightlifting career? It does get frustrating for experienced athletes to see their rate of improvement steadily decrease and sometimes plateau. But give yourself a break. This is a natural phenomenon. It’s not something that you’re doing wrong. It’s simply the way bodies adapt to exercise.

Beginner’s Luck

It’s important to remember a couple things. First, people are different and each person will have a different maximum strength. That is dependent not only on your genetics but your lifestyle as well. If you can only get to the gym twice a week, or you don’t have the luxury to recover like the pros, then those factors will limit your gains. You know how The Rock gets that big? Because he’s paid to get that big. He eats, sleeps, and works out – that’s it. You don’t have that luxury.

Second, most early gains in strength don’t actually come from building muscle. In fact, the reason a beginner can double their bench press in a couple weeks is due to changes in the nervous system! That’s right! In the first few weeks of resistance training, your brain and nerves simply become more efficient at making your body move. I’m sure you’ve heard this saying before. “It takes 6 weeks for you to notice a difference and 12 weeks for the world to notice.” That visible difference comes with a loss of body fat and increases in muscle size. Muscle growth is eventually what causes continued PR’s. But that takes weeks or months to occur.

Neurologic Adaptations To Strength Training

The major improvements in strength during your first few weeks of lifting come from these neurological adaptations. And each of them is covered in detail below:

1: Increased Activation of Synergistic Muscles

2: Decreased Activation of Antagonistic Muscles

3: Increased Coordination of Nerve Signalling

4: Easier Muscle Activation

5: Increased Muscle Firing Rate

Neurologic Adaptation 1: Increased Muscle Synergy

When we start weight training, the body adapts by optimizing the way you activate muscles. Some of this takes place at the level of the brain and brain stem. The brain quickly learns to coordinate muscles better. You unconsciously learn to use synergistic muscles. Synergistic muscles are smaller ones that help the main muscle group. So you are adding more muscles to each movement. Without that, it’s like a tug of war where only the last man on the rope is pulling.

Good coaching can really help with this. Many of the common cues we use while coaching a class are designed to help people learn to use accessory muscles. “Push your knees out!” helps people learn to squat by helping activate gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and tensor fascia lata. Using all of these muscles is key to gaining power in your squat ( and protecting your knees too!)

Neurologic Adaptation 2: Decreased Antagonism

While activating synergistic muscles can be learned and coached, your neurologic system also learns a few tricks on its own. Your brain automatically learns to shut down the muscles that oppose the motion you are trying to perform. Every muscle in your body has a certain amount of resting activation. And when you move, some muscles activate while others “deactivate.”

The muscles in your arm are the easiest to see how antagonists work. Your biceps flex the elbow, and the triceps straighten the elbow. They antagonize each other. When you do a biceps curl, any tone or activation of the triceps will work against the power of your biceps. Activating both is like putting your foot on both the gas and brake at the same time. (Maybe that’s a metaphor that other’s don’t experience much? I mean, with my giant size 14 feet, it happens at nearly every stop light. Wanna spice up your life a bit? Give that a try sometime. I feel like Indiana Jones trying to switch a gold idol with a sack of sand! )

The easiest example is the way your biceps and triceps interact. When you contract a muscle, there’s always some tension on the opposite muscles. The untrained brain isn’t used to relaxing the triceps when you want to generate a lot of power with the biceps. But your brain learns to shut down the triceps pretty quickly. So by decreasing the antagonist muscle tone, your brain is learning to take the brakes off. And that happens very early in weight training.

Neurologic Adaptation 3: Coordinating Nerve Signalling

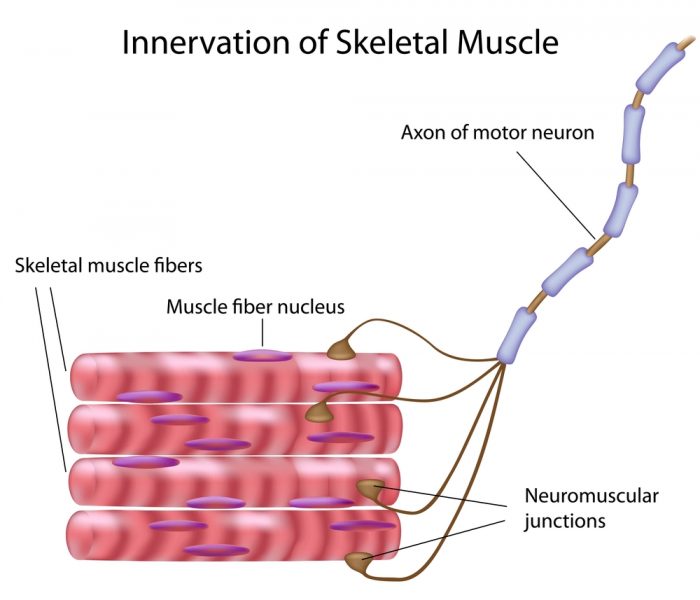

Other interesting changes occur at the junction between nerves and muscles. Every single fiber of a muscle has a nerve ending attached to it. The nerve ending sends a signal to the individual muscle fiber to cause a contraction. Every nerve cell has many small nerve endings: it looks like the branches of a tree. That allows a single nerve to excite multiple muscle fibers.

But when you fire a muscle, it isn’t a one-to-one event. What I mean is that you don’t get one nerve signal that makes your entire muscle contract, all at once, every time. That would be a world of extremes. No finesse at all. That finesse and control comes from firing only the number of muscle fibers required to perform a given task. That’s how you can toss a ball gently to a child or hurl it 100 feet. Fewer fibers activated means less power.

The third neurologic adaptation is how your body learns to fire more of the fibers simultaneously. Instead of just a few fibers haphazardly, your brain begins to tell them all to contract together. And that increases your maximum power!

Neurologic Adaptation 4: Easy Muscle Activation

Your nerves send a tiny electrical signal to cause a muscle to contract. And when you begin weight training, something very interesting happens. The muscles begin to respond to a much lower electrical signal. This means that the muscular response to a nerve signal happens sooner. And it takes less signal for your nerves to cause the muscle to contract. This means that your body can adjust to weight and imbalances more rapidly, which helps you accommodate to greater loads held in awkward positions. Essentially, it makes it easier for your body to balance those large weights! It also helps with the final neurologic adaptation.

Neurologic Adaptation 5: Increase Muscle Firing Rate

When you contract a muscle, it feels like you’re squeezing at the same rate the whole time. But what actually happens is more of a staccato rhythm. The nerve supplying signal to that muscle actually fires many times each second. In an untrained individual, motor neurons typically fire every between 5 and 20 times per second! Yes, you read that right: each muscle fiber contracts on average a dozen times every second! And amazingly in the first few weeks of weight training, those rates rapidly increase.

In young people, the maximum rate of firing improves by 15% or more over 6 weeks of introducing weight training. That translates into a very rapid gain in lifting power! And you’ll remember how we previously talked about the importance of weight training in older individuals. Well, it turns out that older adults can improve the muscle firing rate by nearly 50% over this same training period. Of course, that’s not the only benefit to exercise as you age. If you’ve recently started coaching older athletes, be sure to read our article on specific considerations for those 60 and older here.

Old Dog, New Tricks

These adaptations can only take you so far, but they are responsible for the rapid improvement when people start a new exercise routine. And they are responsible for how frustrated the highly-trained athlete can be when they don’t see the same gains as they did at the beginning. So remember that as your new athletes gain strength quickly and then taper off, it’s totally normal. On average, people see gains of 30% in their max lifts within the first 6 weeks of just about any exercise regimen. But once your brain and nerves adapt to this new challenge, the gains will taper off. But that’s where the real work of coaching and programming comes in. Get to it, coach!

Works Cited

Christie, A, and G Kamen. “Short-Term Training Adaptations in Maximal Motor Unit Firing Rates and Afterhyperpolarization Duration.” Muscle & Nerve May 2010

Griffin, L, and E Cafarelli. “Resistance Training: Cortical, Spinal, and Motor Unit Adaptations.” Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology June 2005

Kamen, G, and C A Knight. “Training-Related Adaptations in Motor Unit Discharge Rate in Young and Older Adults.” The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences., Dec. 2004